The basic idea behind making money with stocks is simple. This is how Joel Greenblatt, one of the best modern value investors, describes it in the Big Secret for the Small Investor: “The big secret to investing is to figure out the value of something — and then pay a lot less”. This is the essence of value investing, and the process we are describing in three key steps:

- Know the price

- Approach the intrinsic value

- Buy when the price is much lower (than the intrinsic value)

This post will focus on the third step – buying at a lower price.

After a long post about approaching the fair value (Step 2), it initially seems that the third step of buying at a lower price is straightforward. While valuation (step 2) is the most challenging aspect in terms of complexity and skill, you don’t need to be an expert in valuation to succeed, and by just being right on average, you may do ok. So, Step 2 may be complex, but I would not say it is the most critical element in the whole process.

The most critical and hardest part is simply making the decision to buy when the price is right, instead of attempting to guess the immediate direction of the stock price. If you fail this part, even the greatest insight and skills won’t save you from doing poorly with stocks.

So, let’s understand why this simple task of buying under the intrinsic value is mentally and psychologically difficult – almost impossible for most people. The stock of Company A, with 1 million shares outstanding, drops from $50 per share to $30 per share, or in other words from $50 million to $30 million market cap (read part one if you are not sure how this works). Let’s assume that your estimate of intrinsic value is around $60 million, and your post-drop reassessment of the company doesn’t find any valid reasons to change this. Very often, a decline is just due to psychological reasons, short-term factors, and money inflow/outflow dynamics.

Of course, sometimes there might be significant reasons that justify the stock price decline, because they have affected the intrinsic value of the company (build a watchlist of your portfolio so that you don’t miss out on any material new information). But, let’s assume that the decline is primarily because of the market dynamics.

A value investor acknowledges these market dynamics, but regardless stays focused on the widening difference of value and price (60-30), rather than caring, evaluating, or guessing the price trend or the absolute bottom. The wider the difference, the wider the margin of safety, and the upside potential. All else being equal, this development should be accompanied by excitement, similar to shopping during sales. Now a business worth $60 million is offered for just $30 million.

Unfortunately, even if most people can intellectually understand this, they cannot really focus and act on it. All their thoughts will be directed to the stock (paper/ticker) and guessing how the price will move, rather than to their shareholding of a business. They cannot escape from the question that their psyche asks: “What will the stock price do?”. This is exactly the question that will prevent them from actually acting appropriately and buying a true business below its value.

A decline in the stock price will make them feel poorer, even though it’s only on paper. Protecting themselves from this trauma, their mind will start thinking of how they can avoid market price losses. Instead of focusing on the bargain arising out of the difference between the price and value, subconsciously, they will be trapped into buying whatever is going up and dumping whatever is going down. The emotional rewards are higher when doing this. However, the monetary rewards are not nice in the long term.

Thus, by focusing on price direction, most investors impair themselves from exploiting the Big Secret we talked about earlier. There are myriad videos and writings of great investors, explaining this over and over again. Intellectually, most people get it, but very few can really embrace and act on it. Typically, they lose their balance and rationality, the same way it happens when they face heights on cliffs and the edges of tall buildings.

One of my friends, a CFA and value investor, describes it very well. Becoming a CFA (Chartered Financial Analyst) is a very difficult task indeed. He says: ”If you put these highly competent and knowledgeable CFAs to read Buffett’s ideas and put them to write a test on it, they will nail it”. However, “only a small minority will be able to implement and act on those ideas.” This is not to disparage this reputable diploma, but to show that carrying out these ideas is not easy, because it depends more on character and less on skill and knowledge.

Very few people have the character to become successful value investors, and a person’s character can’t be easily “retrained”. However, some writings may inspire a change and offer deeper comprehension of the value investing thought process. Even if this philosophy is rarely adopted by individuals, the knowledge of it may help view things from a different perspective.

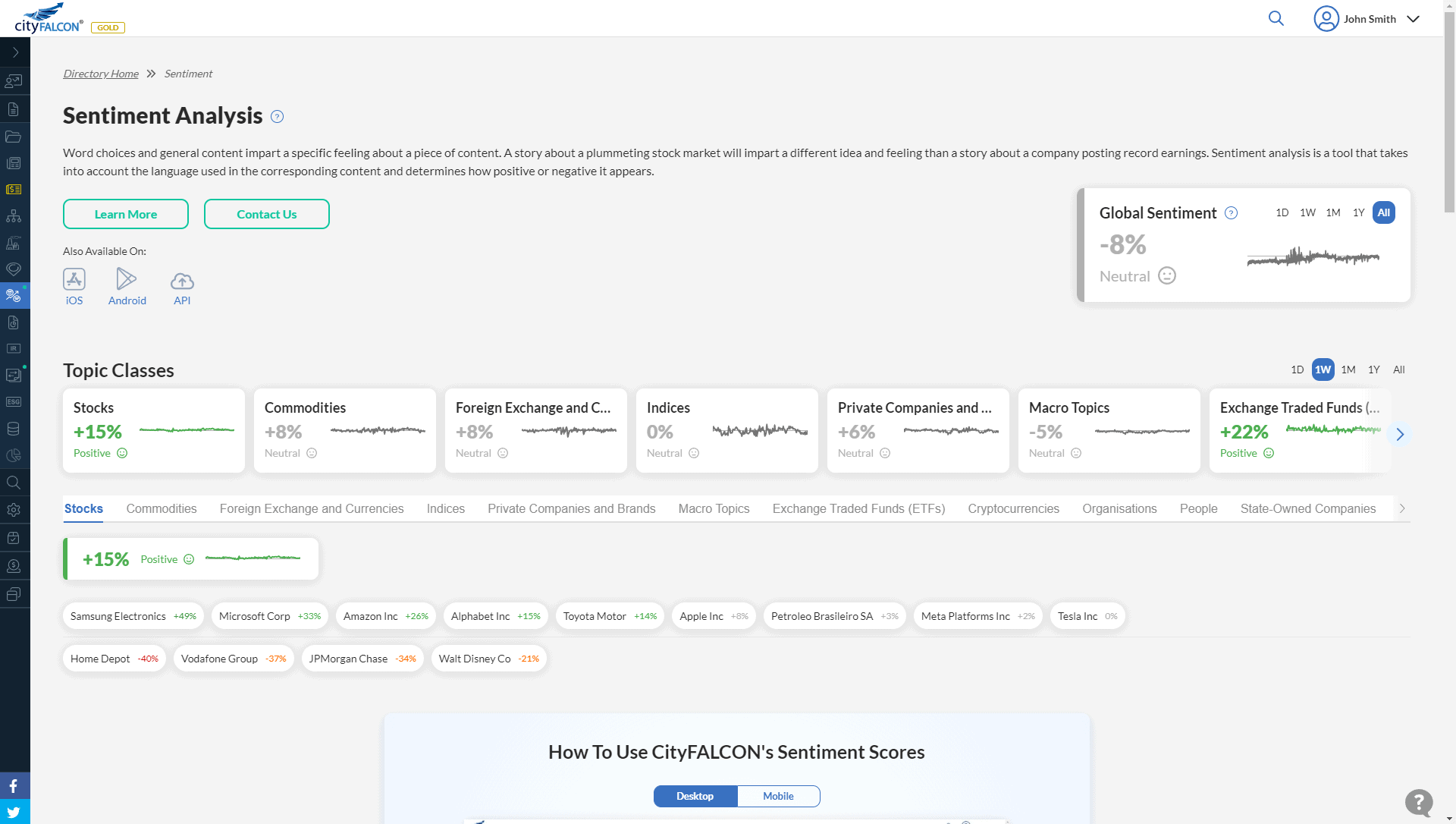

One of the writings of this kind is an allegory invented by Ben Graham. It talks about Mr Market, who is the stock market personified. He’s a manic-depressive salesman who shouts out different prices for stocks at different times. When he’s in a good mood, he’s like an overzealous salesperson, offering stocks at high prices. But when he’s feeling down, he’s more like a desperate salesperson, offering stocks at ridiculously low prices. Monitor his sentiment here.

As an investor, you can take advantage of Mr. Market’s mood swings by recognising that he’s not always rational. When he’s feeling down and offering stocks at a low price, that’s a signal for you to buy them at a discount. And when he’s feeling overly optimistic and offering stocks at a high price, that’s a signal for you to wait for a better deal.

But here’s the thing: you don’t have to predict Mr. Market’s emotions or try to psychoanalyse him to guess future prices. Instead, you just need to see his irrational behaviour as an opportunity to buy low and sell high. It’s like getting a great deal from a neighbour who’s having a yard sale – you don’t need to feel sad if the price keeps dropping, you just need to recognize a good deal when you see one.

So don’t worry about predicting Mr. Market’s emotions or trying to time the market. Instead, stay disciplined and patient, and take advantage of opportunities to buy valuable stocks at a discounted price when Mr. Market is feeling down. He can feel down for reasons that are not related with the long-term value of the companies and their abilities to offer earnings and dividends, such as short-lived events with little long-term impact and the latest news. Looking back in history it’s obvious that these are just noise.

Basically, if you deeply comprehend and appreciate the stake of the company you own, it’s more possible that you won’t feel bad about falling prices but happy (you can pick up more of the stock for less capital outlay). Also, if you can feel as an owner, probably it’s a sign that you have the appropriate character for this job.

This is not a moral judgement. An owner’s mentality doesn’t make you any better as a person. But the stock market is a mechanism that transfers wealth from the people that lack this mentality to the people that hold it. Short term this is not obvious, and it’s “only when the tide goes out do you discover who’s been swimming naked”, as Warren Buffet states.

A crash eventually wipes out the newcomers that thought that the game was short-term and easy. Then people forget, and a new bubble forms with new newcomers that have not learned the lesson yet.

This whole post is the repetition of the same idea. But I truly believe that this is the core of successful investing, and what all legends describe, from Benjamin Graham to Buffett, Keynes, Peter Lynch, Howard Marks, Seth Klarman, and Joel Greenblatt. Despite the repetition, and all historical facts showing how these legends have succeeded, the majority will go the other way. Emotional and psychological security is a very powerful motivator, but the logic of valuation and prices runs counter to them. The fact that so many people act in the opposite way as Buffett describes, even those who understand intellectually, should make you stop and think of the whole concept for a while.

These ideas in this last post in our series are far more important than any analytical skills, if you want to succeed as an investor and be part of the minority that can act differently. So, when a stock goes down, do you ask “how further down will it go?”, or “Is it a greater bargain now?”. I think if you ask the first question, you will rarely be able to buy undervalued stocks, despite any detailed analysis of the company.

So, just go and buy the undervalued thing!

If you want to meet like-minded individuals, searching for undervalued stocks, you may attend our Value Investing Club events, in Malta or London (also live streamed online – past events on Youtube).

Also, try our tools for your favourite stock (for example, Microsoft).

Leave a Reply